By Carly Pepperell

Maps carve borders through landscapes. Clothes are maps for the body. Both are arbitrary constructs, omnipresent in our society, and have a real impact on people.

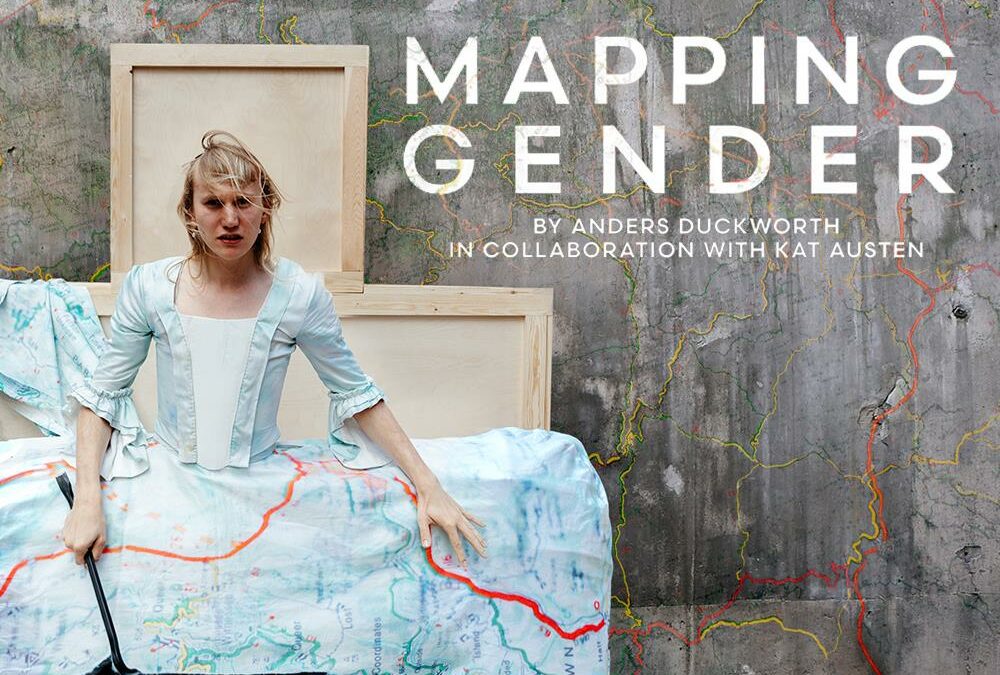

Choreographer and performing artist Anders Duckworth is bringing Mapping Gender to Worthing in February. This multisensory exhibition of dance, image, scent, sound and research is an invitation to explore how, as a society, we draw borders and create boundaries to both carve up geographical space with maps, and divide people with gender.

Mapping Gender has been created in collaboration with sound artist Kat Austen, dramaturg Emma Frankland (who previously performed in Worthing with their production of Hearty), nine interdisciplinary artists, and a group of trans and non-binary volunteers. The show includes selections from a series of recorded interviews with non-binary people discussing their personal experiences. By drawing together people who exist on the margins and the ‘in-between’ spaces, Mapping Gender opens up new possibilities and provides an opportunity to rediscover the place and complexities we find in gender.

WTM’s Carly Pepperell sat down with Anders to talk about everything from the creative development of Mapping Gender to what we can expect to see in the show.

Anders sat across from me, poised and elegant but relaxed and happy, armed with a fresh coffee and flapjack. They explained the process of the production, from first thought to final piece.

“Most of my work is quite convoluted in the way that my process takes me on a journey, and I try not to see the end result. The way I work is like I’m exploring the work itself, which will generate the material that I’m then going to shape and turn into a piece of dance or an exhibit. It can take lots of different forms. But with this piece I had quite a distinctive image – and I do work with images all the time – and I think the quite surprising thing is that this time the image remained. It came to me as more of a shell of an idea, and I’ve just spent the last two and a half years really researching it and trying to figure out what drew me to that image.”

The evolution of dress

The image in question was an 18th century mantua dress that Anders had seen at the Victoria and Albert Museum, where they were struck by the ridiculousness of it and the contradictions that it held.

“It’s a piece of clothing that speaks about power and gender, and those are in conflict sometimes. This piece of clothing spoke to this period in time where we had the beginnings of the British Colonial Empire with the East India Company, and the dress spoke to that kind of relationship of growth and expansion, as well as trade and the desire to present wealth.

“In terms of gender, it’s a highly gendered object; it was really framing the idea of femininity as static and non-moving. So there was this kind of interesting dualism going on, in that its showing its power and domination over the physical space that it takes up, but the person inside is actually quite trapped and reliant on the people around them to work and function in the world. That was my kind of starting point, and I always wanted to connect it to my non-binary experience.

“Seeing the dress invoked a real physical response, which was a mixture between fascination and horror, obsession and love. It was a cocktail of different things. It was such a beautiful dress, but thinking about the people who made the dress and what it represents… there’s so many layers. That particular dress is also interesting because the silk itself was manufactured in France, and at the time there was a ban on imports to England of French silk, so it was somehow smuggled into the UK, and the whole politics of the Spitalfields silk weavers is really interesting. Behind every piece of clothing there’s so many stories, and that’s why it’s really exciting to perform in a museum space which has such an extensive collection of costume.”

Research, collaboration and development

At this point, Anders spoke openly about the progression into collaboration, and the reasons why their collaborators were important and relevant. As Anders is talking, it’s impossible not to listen. Their calculated responses to each question is carefully thought out, ensuring each answer is honest and genuine, making their answers feel almost poetic.

“I guess it was at this point that I started to move in multiple directions. Right at the beginning, I brought on sound artist Kat Austen. She worked with the materiality of landscape and environment, and I was really interested in looking at borders and boundaries in landscapes and how that related to the borders we draw across the body. And of course, the border of gender – the binary notion of gender – was something I wanted to dissect with that metaphor of landscape. There’s a whole history of artists looking to nature and landscapes as metaphors for the body. The thing Kat brought to the work was the sense of environmental costs and implications of nation borders.

“The sounds used in the show come from soil and water samples taken from contested borders, so there’s that kind of thinking about ‘what’s the actual material of those border zones?’ I interviewed someone trained in environmental geography, who gave me the following line that we used in the piece: nature doesn’t have borders, the existing physical borders are imposed by us, and they’re a construct in our heads; the soil and the earth doesn’t know or care what’s happening to it.”

Anders also enlisted the abilities of artist Emma Frankland, who recently performed Hearty at Worthing Theatres.

“I brought on Emma as the dramaturg to really be my outside eye, but also think about how the work is reading and to really probe some of the questions that the work presents. Emma was also there as a support; having a fellow trans person there and being the person who is outside being your mirror and allowing you to see your work was really fantastic. Emma held the space, and when we were heading towards the premiere and there was that crunch point where I was having to step more into that performance role, having that person there to be supportive and think about the care aspect that’s involved in creating work like this was wonderful.”

Exploring perspectives

We had a bit of a break from the interview, and took to discussing the significance of clothing and style, and the conscious decisions we make to display our intent when we dress for the day. I felt that style was a conscious choice, but Anders helped me realise it’s also an unconscious entity.

“I think style is conscious and unconscious, because both actually speak to the power of clothes. With the show, I always wanted to dissect that, and there’s a dismantling of the dress and a notion of borders within the performance. A big part of my process was interviewing non-binary people. We started it in the pandemic; it was a time when a lot of people felt isolated, especially people in the LGBTQ+ community because they weren’t seeing people where they would normally meet in person. We did these interviews – which was a paid position – after we reached out online for people to get in touch. It was amazing. In the end, we were able to interview 12 people, and they came from all over. We had someone from Texas, a refugee from the Middle East, someone from China…

“It was really just wonderful to speak to people with very different perspectives about what it is to be non-binary and how they saw themselves. I was really keen to do that because I know that my voice isn’t the voice for every non-binary person, and I don’t want the show to be a voice for every non-binary person. We took snippets from the interviews which appear in the work, and what they do is provide context but also support me and hold me in the space. Because it’s a solo, it can feel quite sort of isolating, so somehow having those people with me felt really important. I only really understood later on in the process how important that was.

“Honestly I think being a non-binary neuro diverse person as an artist really makes so much sense. Ideas are coming from lots of different places; it takes time to kind of pin those down or arrange those in a way that kind of makes sense. I think spatially, it kind of comes together and makes sense to me, although my thoughts can be very sprawling. It’s very messy. Kat Austen and I would have weekly meetings about the work, and she’s based in South Korea now, so we were working with long distance collaboration and we spent a lot of sessions talking through the ideas. Having Emma come on board to detangle and re-tangle – there was a kind of messiness – which I think is representative of the work. It does physically have this feeling of building, destroying, and rebuilding.”

Translating emotion into art

Following on from the care aspect of creating work like this, Anders spoke candidly about the significance of the emotional vulnerability that’s present.

“My work is always very personal, but this one took it to the next level. I was really talking about my specific gender identity, and although the person people are seeing on stage is me, it also isn’t me. There are moments where I’m channelling other people, which in a way was really comforting to acknowledge trans history.

“The work is internal. It’s happening inside my body, which is why I’m so drawn to dance as one of my art forms. It’s so connected to the body, but also the mind, and it’s important to understand how those are blurred. I’m a very neuro-diverse person, and I think that’s what drives a lot of my need to make work like this.

“One of the questions we asked in the interview was: ‘if you could describe your gender identity as a landscape, what would it look like?’ and it was just very fascinating and beautiful to hear so many interpretations. There were ones that I connected with, and ones that I didn’t, but that didn’t really matter; it’s an internal sense. Because we live in this world which functions around a binary gender system, we don’t really have those conversations around what the landscape and nuances of your gender is. The conversations that are in the public realm around trans and non-binary issues are so reductive. They happen on the terms set by the binary system, so everything is compared to that.

“Something that I wanted to explore was the nuance and sense of excitement that someone might feel when they are discovering new places. I talk a lot about trans landscapes, because the planet is not static. We have tectonic plates moving, land masses shifting, erosions from glaciers; the fabric of the earth is constantly shifting. It’s quite philosophical, that change is actually the one constant.”

Invigorating the senses

We had a brief break, talking about the weather, fashion, and Anders’ perfume, which filled the room with a fresh but woody smell. They explained where they got it from, a French store in London, where the perfumer creates the perfume for you with fresh ingredients while you wait. This led us nicely into the next part of our conversation, which was all about the scent aspect of the performance.

“One of the things that excites me about using smell is that you don’t go to the theatre expecting to smell something. It’s a sense that audience members are less used to employing, so there’s a sense of the unknown. What smell does really well is it allows the possibility of time travel and spatial geographical travel; it’s so linked with our memory. It can really take us to different places, which is what I really wanted for the audiences to experience, particularly looking at smells from the 18th century, with the heavy perfumes. Smell is such a subjective thing, everyone receives it in a different way, and it really excites me.”

Dissecting borders and exploring landscapes

In terms of what Anders feels would be important on what the audience should take away from the performance, it depends on who the audience are.

“I think it depends who’s coming to the show. I would love trans and non-binary people to connect with the sense of frustration and angst but to leave with a sense of inner peace. I’d also like people to be intrigued by this relationship between borders, and for it to maybe open up a way in which people can question the way we put a focus on borders, whether it’s state borders or borders in gender, and just probe those questions about why they are needed.

“I don’t feel like my work particularly says that borders are not useful; I think when they’re a matter of bodily autonomy, to make your own border is really important. Also there’s ways of creating zones or spaces which exist but they’re also open and invite people to come in. There’s different ways that borders can happen, and I think with this piece I’m allowing those borders, but I’m also looking at those really concrete and violent borders, and what happens when people fall between the border zone, and what is it to exist in that space.”