News Story

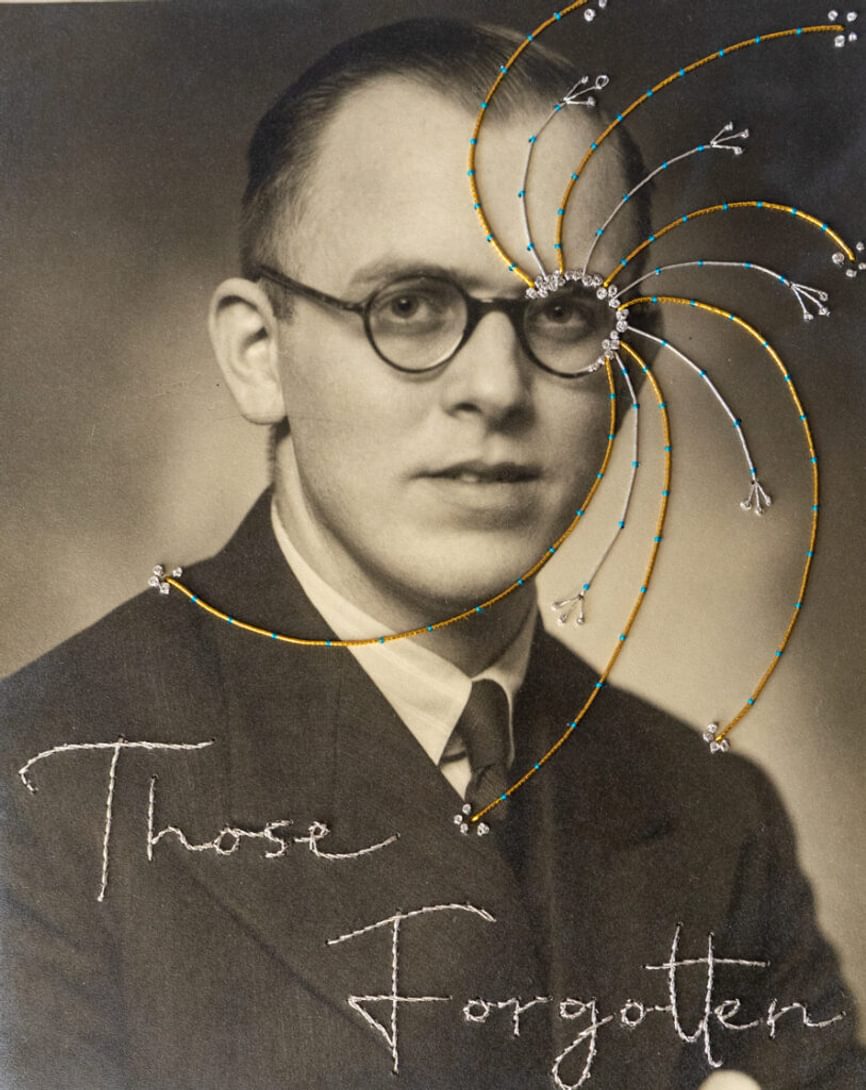

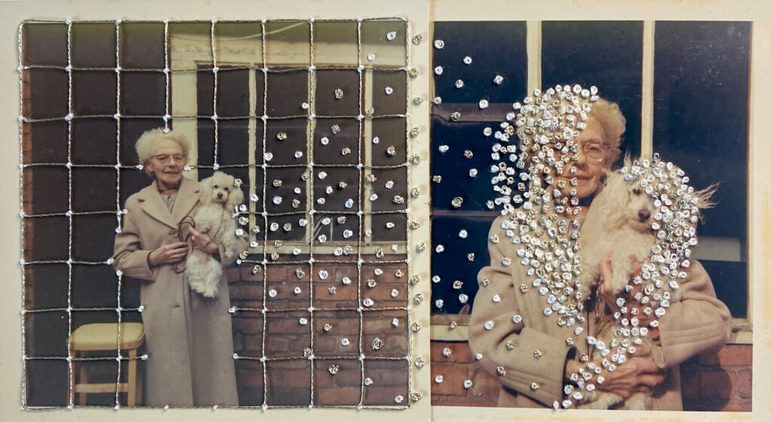

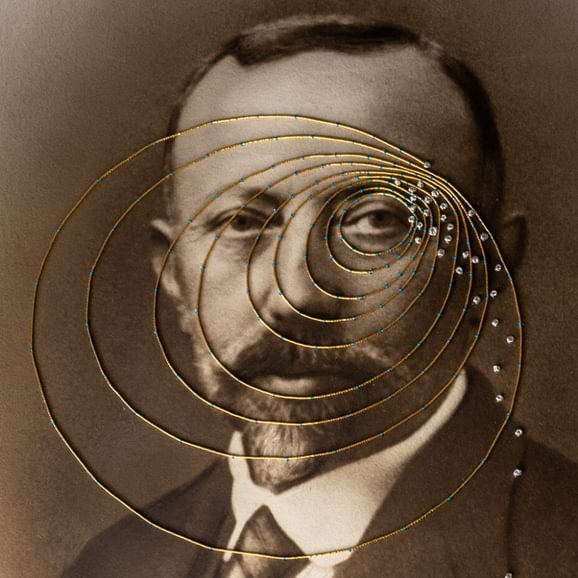

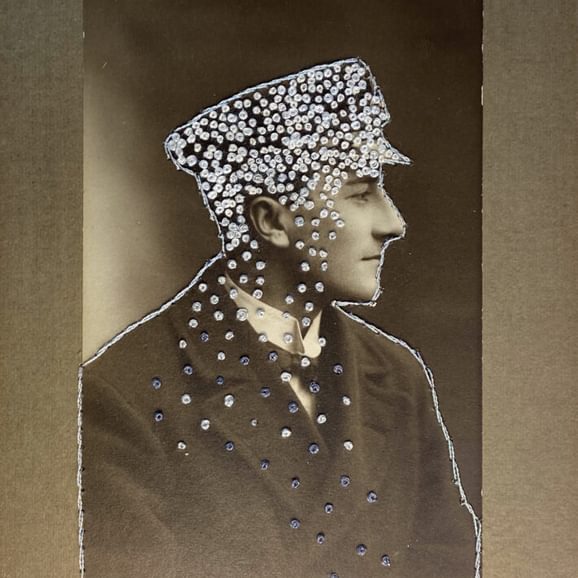

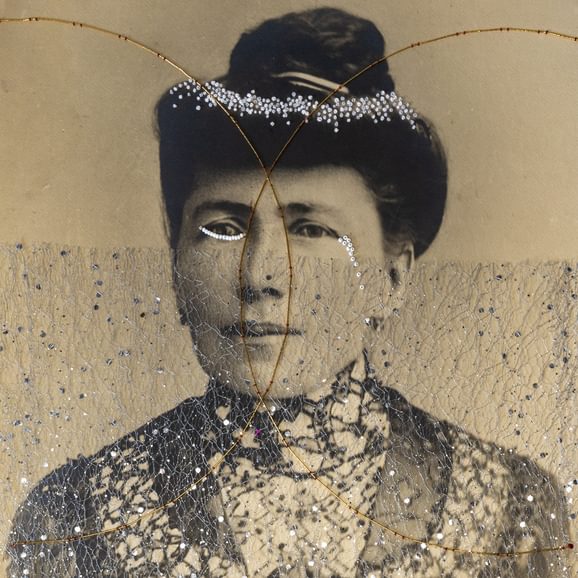

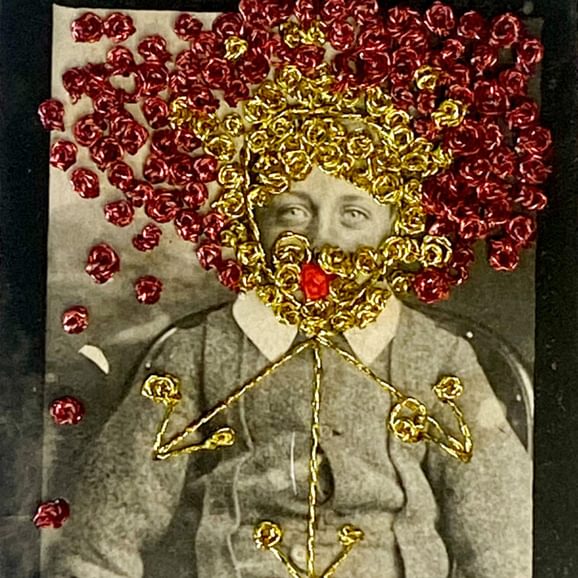

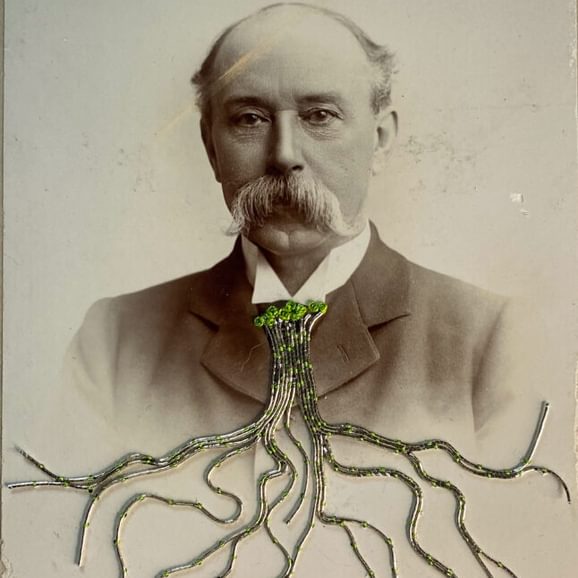

Those Forgotten is a new exhibition at Worthing Museum by textile artist Becky Edmunds. Using historical photographs donated by local members of the public, she has created a collection that breathes new life into photos of unknown people. The project restores beauty and dignity to photos of people whose identities have been lost to time. Find out more about this fascinating mini-exhibition here.

How are you feeling about your upcoming exhibition in Worthing?

I’m really looking forward to showcasing my work at Worthing Museum. This will be my first exhibition featuring photoembroidery, and I’m curious to see how the pieces will look when displayed together.

Tell us about the project, and what inspired you to develop it.

I’ve been working with archival materials for about a decade, primarily as a filmmaker. My interest lies in reusing old materials to create new meanings. A few years ago, I found a collection of diaries in a pile of rubbish. I used these to create a web series, incorporating archival footage to tell the story of the man who wrote the journals. During that time, I also bought some old photographs from eBay. I didn’t end up using them for that project. I kept them around, though.

In 2020, during the pandemic, I took up embroidery and quickly became hooked. Soon after, I began experimenting with stitching into the old photographs, which marked the beginning of a new approach to working with archival materials. I realised that many people have old photographs of people they don’t recognise, often passed down through family. It can be difficult to throw away such photos because they capture moments in time that will never be repeated. So, I decided to invite people to explore their family archives and donate photographs of strangers for this project.

Do you look for anything in particular when choosing these photos? Do you have a selection process?

I buy most of my photographs from eBay, where they are often sold in random collections from various families and eras. I’m always excited to open the packages and discover who’s inside. I’m often drawn to the expressions in the eyes. Studio portraits appeal to me, as they seem to complement the formality of embroidery stitches. I didn’t do much selection with the donated photographs. I accepted whatever came my way, and I’ve enjoyed the challenge of working with more casual family snapshots.

How do you come up with your designs? Are they influenced by the photo itself?

I like to spend some time with a photograph before I start stitching. There’s a process of getting to know the person in the image, trying to get a feel for them before I begin stabbing at the picture with a needle. So, the designs are very much guided by the individual in the photograph.

Do you practice a design on a copy of the photographs before working on the original?

Sometimes I’ll take a photograph of the image and experiment with ideas on an iPad before stitching directly onto the original. Other times, I just begin stitching intuitively.

Tell us more about the process of embroidering photographs.

I start by selecting the threads I’ll use. Sometimes I work with coloured cotton thread, but other times I use metallic threads and beads to add a shimmer to the image. I then pierce the holes using a needle attached to a wooden handle. Once a hole is pierced, it must be filled with thread—there’s no going back! Even when I plan a design beforehand, it often evolves during the stitching process.

Has anything ever changed, or gone wrong during the process?

Yes! Once the holes are pierced, I can’t undo them. So if I make a mistake, there’s no way to fix it. Often, I have to adapt the design based on errors I’ve made.

What’s been the most challenging and the most enjoyable part of this project?

It’s been an interesting experience stitching into photographs that belong to others. Since my usual photos come from eBay, they’ve already been discarded, so there’s no pressure if I make a mistake. However, the donated photos will be returned to their owners, which adds a layer of tension when working on them.

Have people ever told you interesting family stories when they donate photos?

Many of the donated photographs were found at car boot sales or charity shops. One person already had a large collection of embroidered photographs, many of which came from Spain and were popular with tourists in the 1970s. Another individual donated a photograph found in a secondhand book—likely used as a bookmark. One woman donated a postcard her grandfather had sent to his wife during World War I. The front shows a soldier he worked with, while the back contains a story about that soldier. I couldn’t stitch into that photograph, as she wanted to preserve her grandfather’s handwriting, so I had to come up with another solution.

Which is your favourite piece to have worked on?

One of my favourites is a tiny photograph of a young boy, which I stitched back in 2021. It has “The Burlington Midget” written across the bottom, referring to the studio name. During the Victorian era, when photography was becoming more popular, small studios offered cheap photographs for working-class people. The photo is about the size of a passport, and I loved transforming something so small.

Of the donated photographs, I particularly enjoyed working on a formal portrait of a man with a very fine moustache!

Which other textile artists do you admire most?

One of my favourite photo embroidery artists is Yukimi Akiba, who is based in Japan. Her work is astounding! I also admire Julie Cockburn—her use of colour transforms old photographs into stunning abstractions. Michelle Kingdom creates narrative-based work on vintage cloth, and I’m fascinated by Archana Pathak, who creates her own threads from photographs printed on cloth, cutting them into fine strands for stitching. I also appreciate Jordan Cunliffe’s work, which uses embroidery to represent data collection. Judy Chicago’s ‘The Dinner Party’ is a large-scale installation that celebrates exceptional women throughout history through embroidery. Textile art is led by inspiring women, and I find the creativity in contemporary embroidery thrilling.

What advice would you give someone who was interested in learning more about embroidery?

Start by searching for #embroidery on Instagram—you’ll be amazed at the creativity in contemporary embroidery. While embroidery has a reputation as a domestic craft, artists today are using thread to create exciting and often subversive expressions. I also recommend trying it yourself. It’s a wonderful way to spend time. I love listening to an audiobook while spending an afternoon with a needle and thread. There are many artists who create lovely kits with instructions. And YouTube is full of tutorials to help you learn the stitches. I will be running workshops at Montague Gallery for those who want to get started with embroidery. You can sign up to my newsletter to find out when the next workshops will be held.

Tell us about any other projects you are working on.

I’m currently collaborating with a group of artists on a project called *We Are All Memory Bodies*, led by Brighton-based dance artist Charlotte Spencer. The project explores how the body stores memory, inviting audiences to engage in activities that may reawaken memories. I’ll be inviting people to stitch their DNA into fabric.

I’m also experimenting with light-reflective fabrics and threads. I’m working on a series of pieces that will shine when exposed to sunlight.

What do you hope audiences will take away from this show

I hope people are inspired to explore their own photographic archives. And perhaps use some of the photos they feel less attached to as materials for creating new art.

Those Forgotten is on at Worthing Museum 19th October – 26th January and will be displayed in the Norwood Landing space. To find out more about the project and upcoming photo embroidery workshops, visit Becky’s website.