Carola Del Mese, metal conservator

I have been invited to conserve some objects from Worthing Museum archaeology gallery, and in the last post I went through the objects, explaining what they are, where they were found and how old they are. In this post we will be taking a much closer look, as part of the conservation process called ‘assessment’.

What is a condition assessment?

In these last two posts I will be showing conservation of the historic grave goods from Highdown Hill. In previous posts we discussed the objects chosen for conservation and the assessment process. Here I will be talking through the conservation treatment of some of those objects and a little about the reasoning behind those decisions from a conservation point of view.

To treat or not to treat?

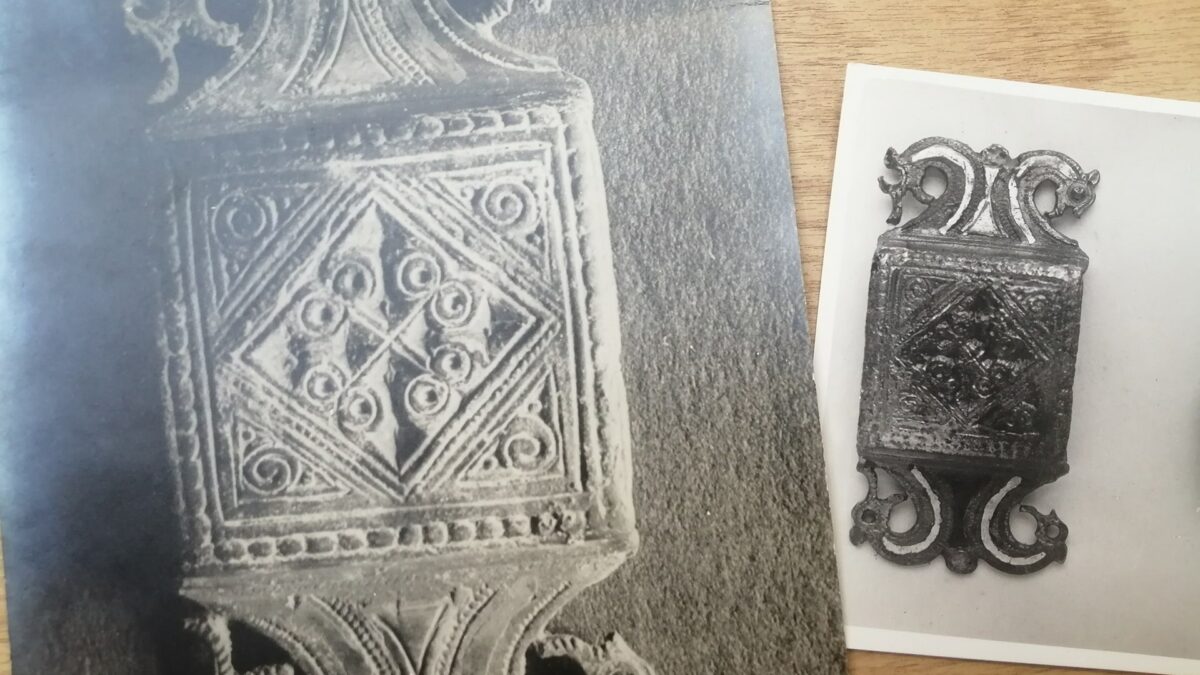

No conservation treatment should risk any unnecessary change or damage to the objects, and the assessment showed that none of the objects were actively corroding, meaning that very little intervention was necessary. All the objects are kept in environmentally controlled display cases, so light and humidity are at optimum levels to avoid degradation. We compared the objects’ current conditions with accession photographs taken in the 1980s and photos taken in the early 20th century, immediately after excavation. This showed us that all the visible damage had happened in the years between excavation and accession to the museum, confirming that the museum environment is very stable and minimal intervention was needed.Excavation images compared with accession images, showing damage which occurred prior to accession.

During assessment, we discovered that most of the objects had been coated with either wax or lacquer while in private hands, and that these coatings had degraded. When this happens, the coating is no longer providing protection, and could cause the surface to become discoloured and patchy, where some areas are exposed to the environment and can oxidise, and some areas are protected. Most of the objects simply needed a surface clean and removal of the old coating, then re-application of a new, conservation coating.

Stabilising a Bronze Age ring

In the Bronze Age case, this copper alloy ring which is part of the Stump Bottom Hoard had developed a pale green surface. This is a type of very slow corrosion, and is generally stable, we see this clearly in the green corrosion which develops on copper objects, commonly referred to as Verdigris. If an object has a protective coating such as a lacquer, it is protected from corroding, however over time the coating will degrade and the copper will generally develop brown, then green layers. The other copper alloy objects from the hoard were either dark brown or dark green and stable, suggesting that they had a protective coating, while the ring did not.

The ring’s surface was fragile and needed consolidation to avoid disintegration. I first slowly dripped IMS (industrial methylated spirits – a solvent) onto the area I wanted to treat, following it quickly with drops of a solution of 5% Paraloid B72 (a conservation adhesive) in IMS, then repeating this with the next area. The first drops of pure IMS were to wet the porous internal matrix of the object, helping to carry the consolidant into the object. I used IMS as opposed to acetone as it evaporates more slowly, allowing the consolidant to travel further into the powdery areas before curing. This treatment darkened the surface slightly, but the object is now more stable than before.

Surface cleaning the Sussex loops

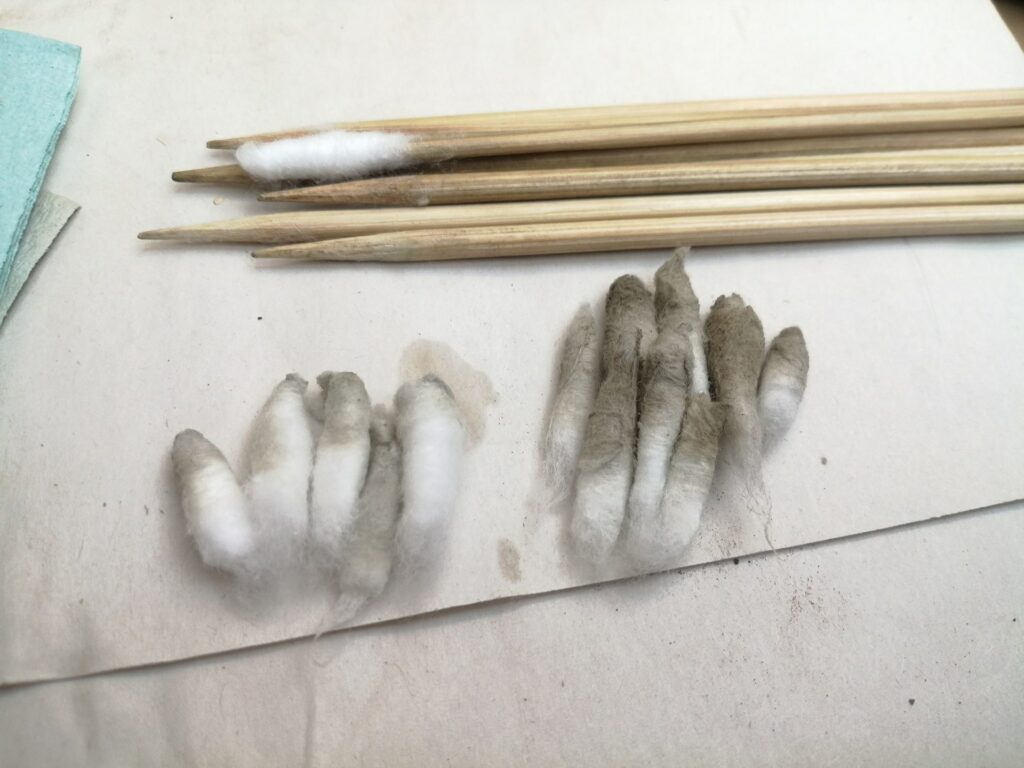

The Sussex loops were showing remains of a waxy coating in places, while some areas were dusty, with remnants of soil from the original excavation, and some pale green corrosion spots. Surface dirt is a risk to the object as it can attract dust, then moisture, possibly micro-organisms and encourage corrosion. No loose corrosion was visible, so the corrosion spots were not active. The surface was mainly dark green and stable, but could be easily scratched, and so surface cleaning would need to be gentle.A closer look also reveals some interesting manufacturing details. Some of the angles have been deliberately flattened, to stop the metal bulging out when the loop was created, and to make the interior of the loop smoother. There is also a deliberately hammered-in (‘chased’) line running along the entire length of one of the sides. It appears to have been smoothed or sanded away as if the maker changed their mind about this decoration.

Anatomy of a Saxon belt buckle

This heavy belt buckle showed some interesting features during assessment. I initially assumed the white metal was pewter or lead which appeared to have been cast around an iron core. Repairs had been cast onto the buckle with a slightly yellower alloy, and there were obvious filing marks on the surface – whether this had been done in antiquity or post excavation was unknown. We could also see that a lacquer layer had degraded and become cloudy, therefore needed removal and re-application.

This object was one of a selection taken to West Dean College for elemental analysis, and by using XRF (X-ray fluorescence), we discovered that the white metal was actually leaded bronze. Bronze is usually an alloy of Copper and tin, however the buckle also contained around 4% lead, which with the 6% tin, had sufficiently changed the colour of the metal to appear silvery. The addition of lead would also have enabled easier casting and cold working of the metal. Acetone swabs removed the old coating, and for protection I applied a new coat of 10% Paraloid B48 in acetone.

In part two of this post I will go through conservation treatments undertaken on two more of the objects from Highdown Hill.

The assessment and conservation of these objects, safeguarding them for future generations, was made possible by a grant from the South East Museums Development Fund, and Arts Council England.

By cross referencing the archival images of these brooches, we can see how much they have degraded since their excavation. The square brooch with the chased details was once intact, and was broken and repaired before its donation to the museum. The round brooch has suffered some loss between the original images and those taken in the 1980’s. By examining that area under magnification, I discovered that it is fragile and cracked, suggesting that I could use a conservation glue to strengthen the area.

Images: Carola Del Mese and Worthing Museum