Carola Del Mese, metal conservator

I have been invited to conserve some objects from Worthing Museum archaeology gallery, and in the last post I went through the objects, explaining what they are, where they were found and how old they are. In this post we will be taking a much closer look, as part of the conservation process called ‘assessment’.

What is a condition assessment?

The aim of assessment is to closely examine the object, to learn as much as possible about it, which helps to decide the most appropriate conservation treatment – if any. The information is then entered into a condition report which can be referred to by any future conservator, researcher or curator, creating a detailed record of the object.

What will we discover during assessment?

Close examination can help us to understand the manufacturing process, the materials, any vulnerable areas, previous repairs, active corrosion or degraded coatings. This information will help to build a fuller picture of the object and potential issues leading to treatment options. In the case of archaeological objects, assessment may also shed light on the technologies, trade links and communities who used the object.

How do we assess objects?

Assessment can include cross referencing previous treatments, material analysis (what it is made of), considering future environmental conditions (where it will be stored or placed and how it may be displayed or used), any ethical considerations (in the case of religious or objects from certain cultures) and crucially, the condition of the object itself – is the object actively corroding or deteriorating in any way, and does it need intervention?

Conservators use a variety of analytical methods to assess objects, depending on the information needed and the resources available. These might include visual and microscopic examination, X-ray imaging, UV light and more scientific methods used in conservation laboratories.

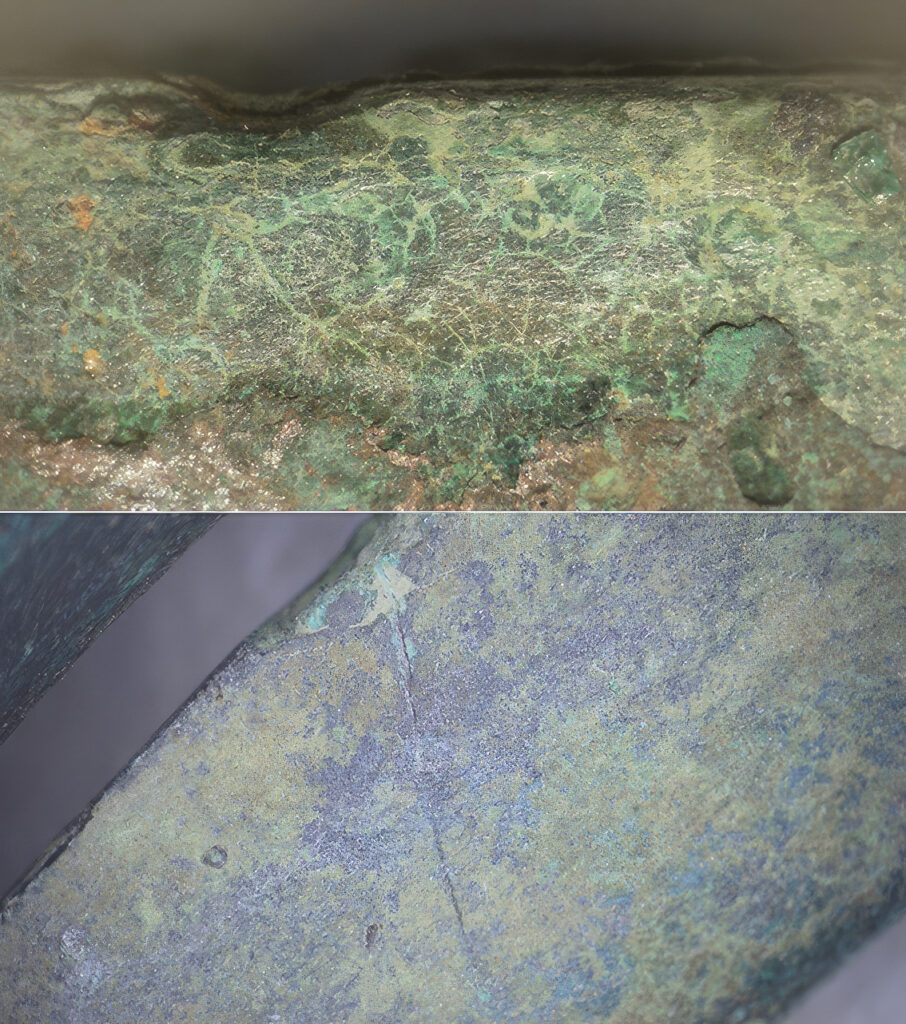

Here at Worthing Museum, I have used photographs from the archives, close visual examination, and a small digital microscope camera which can be plugged into a laptop. The close-up images provided by the microscope have revealed some interesting information!

What did we see?

Sussex loops

The beautiful Sussex loops from the Bronze Age display are approximately 3500 years old, and in incredible condition considering this. On first glance they appear to be stable although there is some surface corrosion, and by carefully handling them, they appear to be structurally sound. However, when I used the microscope, I could see some worrying hairline cracks, telling us that the metal is losing its metallic qualities and becoming brittle. This means that the object is vulnerable and handling it could risk further damage, so this information will be recorded in the report.

A closer look also reveals some interesting manufacturing details. Some of the angles have been deliberately flattened, to stop the metal bulging out when the loop was created, and to make the interior of the loop smoother. There is also a deliberately hammered-in (‘chased’) line running along the entire length of one of the sides. It appears to have been smoothed or sanded away as if the maker changed their mind about this decoration.

Ferrule

A ferrule is the metal band which holds the hairs onto the tip of the brush, and this one is Roman. The handle no longer exists, but by looking through the microscope into the gap, we can see in detail, the remains of coarse hair – probably hogs hair – previously undocumented, from around 1500 years ago!

Quoit brooches

The detail on these brooches comes alive when seen under magnification, showing that the wavy lines are made of lots of smaller, straight lines. This means that the technique used was ‘chasing’, where a small tool punch is hammered on to the metal surface repeatedly, to create decorative lines and indentations. It’s fascinating that this ancient method is still commonly used today by metal craftspeople.

By cross referencing the archival images of these brooches, we can see how much they have degraded since their excavation. The square brooch with the chased details was once intact, and was broken and repaired before its donation to the museum. The round brooch has suffered some loss between the original images and those taken in the 1980’s. By examining that area under magnification, I discovered that it is fragile and cracked, suggesting that I could use a conservation glue to strengthen the area.

Belt slide

This item is of specific interest to the museum, as research suggests it is unique. It has very fine detail on the front, and horse or dragons’ heads inlayed with silver at the top and bottom. An image of the object immediately after excavation shows it in perfect condition, however, some of the detail has since been lost. Examination under the microscope shows a strange, melted texture, unlike regular corrosion and without the powdery residue expected on actively corroding metal.

By comparing the original images with the ones from the 1980s, we can see that the damage occurred before its donation to the museum, and the object still looks exactly the same 40 years later! This also shows us that the environmental conditions in the display case are excellent for preserving the objects.

In my next blog post we will be looking at the treatments I carried out on some of these objects as a result of the assessment, and the decisions behind them.

Images: Carola Del Mese and Worthing Museum